Staying Safe Abroad: What Travelers Need to Know About Lassa Fever Prevention

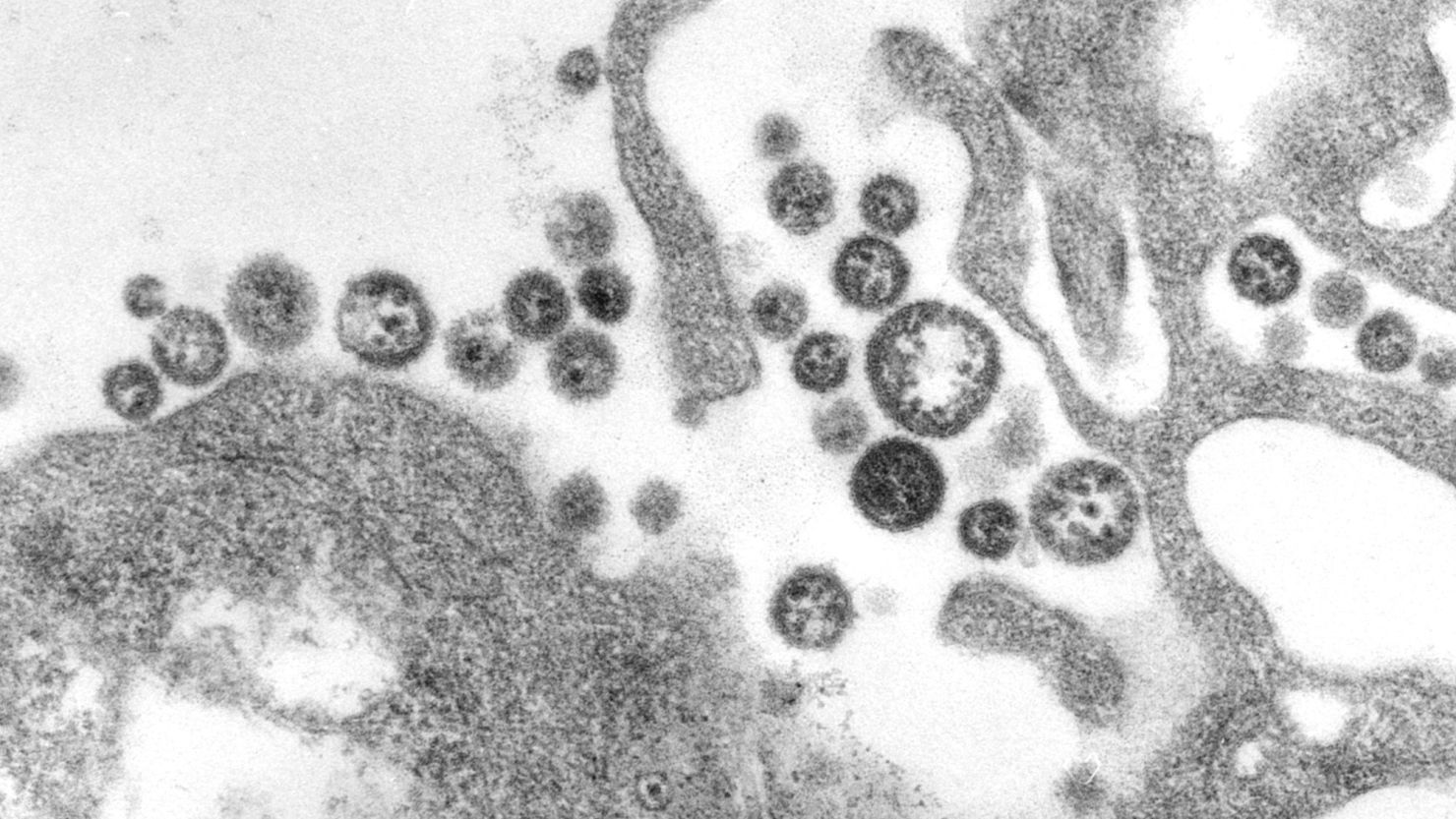

USA NEWS – The recent death of an Iowa resident after returning from West Africa has sparked renewed attention to Lassa fever, a rare and potentially deadly viral illness more common in parts of West Africa. According to Iowa’s Department of Health and Human Services, the middle-aged individual was confirmed to have contracted the virus during their travel and passed away shortly after their return to the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stated that the transmission likely occurred through contact with rodents, which are the primary carriers of the virus in endemic regions.

The case, which highlights the risks associated with certain global travel, has prompted health authorities to take swift action. Lassa fever, categorized as a viral hemorrhagic fever, does not spread casually like the flu or COVID-19. According to the CDC, Lassa fever can only spread from person to person through direct contact with infected body fluids, such as blood, saliva, urine, or vomit. This particular case is rare in the U.S.; only eight travel-related cases of Lassa fever have been reported domestically over the last 55 years, underscoring the unusual nature of this infection in the country.

Since the infected individual did not display symptoms while traveling, health officials stress that the risk to other passengers on the flights remains extremely low. Dr. Robert Kruse, Iowa’s state medical director, reassured the public, noting, “The risk of transmission is incredibly low in Iowa, and we continue to monitor the situation carefully.” Symptoms of Lassa fever generally manifest one to three weeks after infection, meaning that an individual may unknowingly carry and develop the virus sometime after exposure. The CDC is currently working alongside state health departments to identify any individuals who may have come into contact with the infected person after they developed symptoms, and close contacts will be monitored for the next 21 days to ensure containment.

Lassa fever is known to be endemic in several West African countries, including Sierra Leone, Liberia, Nigeria, and Guinea. Every year, between 100,000 and 300,000 cases occur in these regions, resulting in approximately 5,000 fatalities. The disease primarily spreads to humans through contact with the urine or feces of multimammate rats, which are commonly found in rural areas. These rats can often enter homes or food storage areas, creating frequent opportunities for human contact with the virus. In cases where Lassa fever is transmitted between people, it is typically through direct exposure to bodily fluids rather than casual interactions, such as handshakes or hugs. This makes the virus less contagious than other viral hemorrhagic fevers, such as Ebola or Marburg virus, which are more easily spread.

Despite its lower transmission potential, Lassa fever poses significant health risks, particularly in areas with limited medical resources. The CDC has stated that the fatality rate for Lassa fever is approximately 1% overall. However, among patients who require hospitalization due to severe symptoms, the fatality rate may rise to as high as 15%. For patients in endemic regions, complications such as organ damage, respiratory distress, and severe bleeding can lead to higher mortality rates. Moreover, for pregnant individuals, the risks are particularly severe, with nearly 95% of fetuses unable to survive Lassa fever infections during pregnancy.

The Iowa case follows a year marked by increased awareness of viral hemorrhagic fevers globally. Recently, Rwanda experienced an outbreak of Marburg virus, a deadly hemorrhagic fever closely related to Ebola, infecting over 65 individuals and leading to 15 fatalities. While Lassa fever is considered less fatal than Ebola or Marburg, its prevalence in West Africa and occasional spread to other parts of the world through travel remain public health concerns.

A key challenge with Lassa fever is diagnosis. Symptoms often vary and can be mild, making it difficult for healthcare professionals to distinguish Lassa fever from other viral or bacterial illnesses. Common early symptoms include low-grade fever, fatigue, and headaches, which can easily be mistaken for less serious infections. In severe cases, patients may experience bleeding, facial swelling, and chest pain, symptoms more indicative of hemorrhagic fever. The CDC and World Health Organization (WHO) report that mild Lassa fever cases can sometimes resolve on their own, but more severe cases may require intensive medical intervention.

Currently, there is no licensed vaccine for Lassa fever, which has motivated public health agencies to focus heavily on prevention. In endemic regions, prevention primarily involves limiting exposure to rodents by keeping living areas clean and storing food in rat-proof containers. Some communities in West Africa have also been educated on proper hygiene practices to minimize human-rodent interactions. The CDC also advises travelers to exercise caution when visiting regions where the virus is known to be present, recommending avoidance of potentially contaminated food or drink and staying away from areas where rodents are common.

In the U.S., healthcare providers follow stringent protocols when dealing with suspected cases of viral hemorrhagic fevers. The Nebraska Public Health Laboratory, which first tested the Iowa case, is currently collaborating with the CDC to confirm the diagnosis. Due to the nature of the virus, healthcare workers take extensive precautions when treating patients with suspected Lassa fever, including using personal protective equipment to prevent accidental exposure. Medical samples are handled with care, and testing is conducted in highly controlled environments to prevent the virus from spreading further.

Treatment for Lassa fever is currently limited but includes options that may improve patient outcomes when administered early. Ribavirin, an antiviral medication, has shown effectiveness in treating Lassa fever, but its success depends largely on early intervention, which can be difficult given the virus’s non-specific symptoms. Supportive care, such as hydration, rest, and treatment of symptoms like fever and pain, is also recommended to help the body fight off the infection. For healthcare providers, diagnosing Lassa fever remains challenging because it shares symptoms with numerous other infections, but advanced laboratory testing can identify the virus in cases where there is a high index of suspicion.

Experts emphasize that while Lassa fever is a severe disease, its impact is generally contained within West Africa. Dr. Albert Ko, an infectious disease specialist at Yale School of Public Health, noted, “This is a disease that is very serious and significant in Western Africa, but it is not one that is easily spread from one place to another.” Unlike more easily transmissible viruses, such as COVID-19, which can spread through respiratory droplets, Lassa fever requires direct exposure to contaminated fluids. This limitation reduces its potential to cause widespread outbreaks outside of endemic areas. Nonetheless, health officials in the U.S. continue to monitor travel-associated cases closely to prevent any potential transmission domestically.

As public health officials work to contain this case, they are urging awareness and caution among those who may be traveling to areas where Lassa fever is common. The CDC recommends taking preventative measures, such as storing food securely and avoiding direct contact with rodents or areas where rodents are likely to reside. They also advise travelers to be aware of symptoms and seek medical attention if any feverish or unusual symptoms occur after returning from a high-risk area.

The Iowa Department of Health and Human Services, University of Iowa Health Care Medical Center, and CDC have each played a critical role in responding to this case. They have closely coordinated efforts to ensure that potential contacts are informed and that adequate precautions are in place. While this situation is undoubtedly tragic, officials hope it serves as a reminder of the importance of public health vigilance and the role of preventive measures in controlling the spread of infectious diseases.

With the increasing movement of people globally, health experts expect sporadic cases of diseases like Lassa fever in non-endemic regions, though the risk remains low. Public health education, early detection, and proper containment procedures are essential in minimizing the spread of rare but serious diseases in the future. The CDC continues to work with international health organizations to monitor infectious disease trends and improve preparedness for rare cases like this.